I’ve been toying with the idea of a mash recirculation setup for my system recently. Using some sort of mash recirculation system gives you much finer control over mash temperatures. In an infusion mash, the kind I do now, the temperature of the grain and the ratio of water to grain are plugged into brewing software (or thermodynamics equations if you’re wiggy like that) to calculate how hot your strike water needs to be to achieve your desired mash temp. For example, 10 lb of grain sitting at 72°F with a 1.25 qt/lb ratio would require 166°F strike water to achieve a mash temp of 154°F, according to BeerSmith.

The problem with this process is that it can be pretty tough to hit your mash temperature exactly. If you brew enough on the same system, you can tweak your process until you nail it pretty consistently, but there will always be hot and cold spots in the mash which makes getting an even temperature across the entire mashtun difficult. I’m usually off by a degree or two – not a huge deal, but it does add some variance to my brew sessions. Even if you do manage to hit your desired temperature exactly, the mash is going to cool over time. My mashes typically last one hour, and I’ll see a temperature drop of anywhere from one to five degrees using a converted Coleman cooler as my mashtun – more if the ambient temperature is really cold.

Now, this isn’t the end of the world, and for many homebrewers it won’t even be a concern. However, if you are looking for exacting control over the mash process, recirculation is the way to go. I see several benefits to using a mash recirculation system:

- the mash temperature can be raised in step mashes without additional water infusions

- the mashout temperature can be reached without additional water infusions

- the strike and mash temperatures can be easily reached and accurately maintained throughout the entire mash

- an even temperature can be maintained across the entire grain bed

However, there are also some drawbacks. Mash recirculation requires extra equipment, like a pump and a heating element. It also makes your setup that much more complicated – the more moving parts and steps in your process, the more likely something will go wrong at some point. So the question seems to be: Do the pros of mash recirculation outweigh the cons? That very debate has been hashed to pieces in brewing forums across the globe.

Personally, I’ve never had any problems doing plain old infusion mashes. To go buy a pump and rig up a heat exchanger seemed like a solution looking for a problem. However, I now own a March pump (which I find indispensable during the brewing process) and I’m always looking for new ways to use it. Also, as I tackle more difficult and delicate beer styles, such as Kölsch and other light lagers, I can appreciate the benefits of more precision during the mash. So, I’ve decided to revisit the idea of recirculation, while trying to keep it as simple as possible.

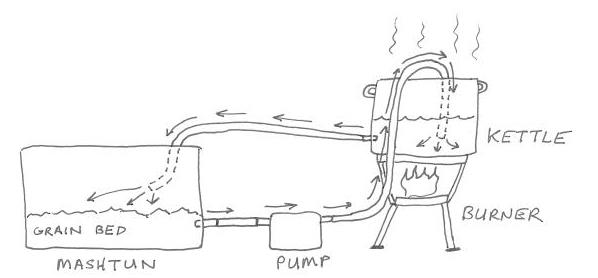

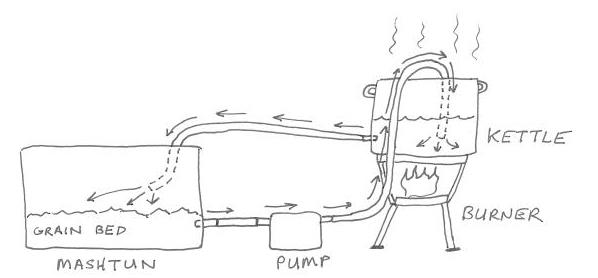

I’m not sure if this will work the way I hope, and I can’t even take credit for the idea – it came from a thread on Morebeer’s forums, where the author described a method his homebrew club uses to reach mashout temperatures during their brews. Basically, it’s a poor (or lazy) man’s RIMS setup, using the boil kettle to apply direct heat instead of a heating element. The pump pulls wort from the mashtun and pumps it into the heated kettle, with the idea that the whirlpool action the pump’s output creates will keep the wort moving and avoid any scorching. The wort is then gravity-fed from the kettle’s spigot back to the mashtun (see diagram below). Temperature feedback is provided via thermometers placed in the kettle and mashtun, while careful use of the kettle burner heats the wort to the proper temperature. The output flow of the pump can be restricted to match the output flow of the mashtun, keeping the system in balance and the level of wort in the kettle constant.

This lacks a lot of the automation and precision of a true RIMS or HERMS design, but I think it would be more precise than infusions and doesn’t require any additional equipment. I see a few potential problems that may need ironing out:

- will I need a sparge arm to evenly distribute the recirculated wort over the grain bed, to prevent channeling and inconsistent temps?

- any possibility of hot-side aeration? (I don’t really believe it’s a problem on the homebrew level, but can’t pass up the opportunity to freak out the HSA fear mongerers)

- will a stuck sparge/clogged manifold be more of an issue than usual?

- how difficult will it really be to maintain a steady temp using the direct heat method?

Obviously, this needs some empirical testing to see how well it works, but I am optimistic. I will perform a few experiments next week and report back with my results. Eventually I’d like to go to a real HERMS system, but I’m a ways off from that and this could be a nice compromise.

Note to novice brewers – don’t worry about all of this yet. Having a recirculation system will not replace actual skill and magically produce great beer, just as not having one will not prevent you from making great beer. In fact, I eschew any kind of automation until you have your basic skills down.